SEOUL — In a landmark decision poised to fuel the nation's ongoing debate on judicial and prosecutorial reform, the Ministry of Justice has invoked the Standing Special Prosecutor Act to investigate two high-profile allegations of misconduct within the South Korean prosecution service. Justice Minister Jung Sung-ho announced on October 24 the decision to appoint a special counsel to probe the 'loss of the Bank of Korea's sealed bundle of new banknotes wrapper' in the Seoul Southern District Prosecutors' Office and the 'alleged external pressure to drop the investigation into Coupang severance pay' in the Incheon District Prosecutors' Office Bucheon Branch.

This move marks a historic first on two fronts: it is the initial instance of the Standing Special Prosecutor, introduced in 2014, being launched solely by the Justice Minister's decision, and it is the first time a special counsel has been established specifically to investigate the prosecution service itself.

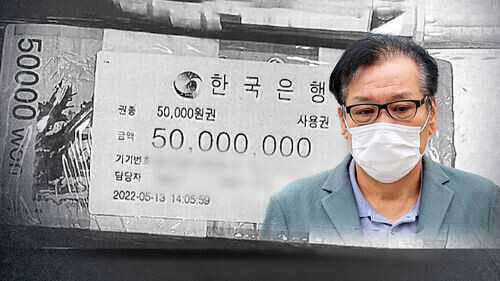

The 'sealed bundle wrapper' case involves the disappearance of a wrapper and sticker from new banknotes seized by the Seoul Southern District Prosecutors' Office in December of the previous year from the residence of shaman Jeon Seong-bae. While an internal inspection by the Supreme Prosecutors' Office concluded that there was no "intentional concealment or instruction" from senior prosecutors, public skepticism intensified, with critics alleging a "cover-up." Similarly, the 'Coupang pressure' allegation—which came to light through the internal exposé of a senior prosecutor—concerns potential external influence on the decision to drop charges against Coupang Fulfillment Service for the non-payment of severance to temporary workers.

Minister Jung explained the decision's rationale on his social media, stating, "Both cases involve suspicions that the prosecution attempted to distort the truth... It was determined that the prosecution's self-inspection alone could not secure the public's trust." This activation of an independent, external investigative body is seen as a deliberate attempt to overcome the perennial issue of the prosecution service investigating itself, thereby mitigating accusations of "shielding its own."

The influence of President Lee Jae-myung is also believed to be a factor. Following the emergence of the banknote wrapper controversy, President Lee reportedly instructed Minister Jung to "review alternatives, including the Standing Special Prosecutor." After the internal inspection results were announced, the President publicly criticized the situation, stating that "public officials in justice institutions, who should be fair and impartial, are disturbing the national order by covering up illegalities." The Minister's swift decision followed immediately after this public statement.

These two cases represent the 19th special counsel investigation since the system's introduction in 1999, which has primarily focused on political and economic scandals. Their referral to a special counsel now elevates them to a critical juncture for the ongoing legislative efforts toward prosecution reform. If the special counsel uncovers evidence of high-level external pressure or intentional investigative malpractice, it will significantly bolster the ruling Democratic Party and civil society groups' calls for a fundamental restructuring of the prosecution's immense power. The Citizens' Coalition for Economic Justice (CCEJ), in a statement, asserted that the cases "reconfirmed the reason why prosecution reform, which decentralizes the overbearing authority of the prosecution, must be pursued."

Under the Special Prosecutor Act, the investigation will be led by a special counsel recommended by the National Assembly's Special Prosecutor Candidate Recommendation Committee—a seven-member body comprising the Vice Minister of Justice, the Chief of the Office of Court Administration, the President of the Korean Bar Association, and four members recommended by the National Assembly (two from each major party). The President must appoint one of the two recommended candidates within three days.

The special counsel team can be composed of one special prosecutor, up to two assistant special prosecutors, five dispatched prosecutors, and up to 30 dispatched public officials and special investigators each. The investigation period can last up to 110 days—a 20-day preparation period, a basic 60-day investigation, and an optional 30-day extension subject to presidential approval.

The speed of the special counsel's launch remains a key question. The first special counsel under the Act, for the Sewol Ferry disaster, faced over four months of delays in forming the recommendation committee due to partisan disagreements. However, the outcome of this unprecedented investigation into the prosecution's internal affairs will undoubtedly shape the future trajectory of South Korea's judicial landscape and the scope of its most powerful investigative body.

[Copyright (c) Global Economic Times. All Rights Reserved.]