Colombia- A damning two-year investigation culminating in a comprehensive report, a BBC documentary, and a whistleblower dossier has cast a dark shadow over Colombia's state-owned oil company, Ecopetrol. The exposé, titled "Crude Lies" and published by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) in collaboration with Earthworks, alleges widespread environmental contamination, significant health impacts on local communities, and systematic efforts by Ecopetrol to conceal pollution and surveil affected residents in the oil-rich Magdalena Medio region.

The findings are corroborated by the "Iguana Papers," a trove of internal Ecopetrol documents leaked by Andrés Olarte Peña, a former petroleum engineer and environmental advisor within the company. Olarte Peña, who worked under the supervision of then-CEO Felipe Bayón and Vice-President of Sustainability Eduardo Uribe between 2017 and 2019, witnessed firsthand what he describes as the company's severe harm to local populations. Facing death threats, Olarte Peña now lives in exile.

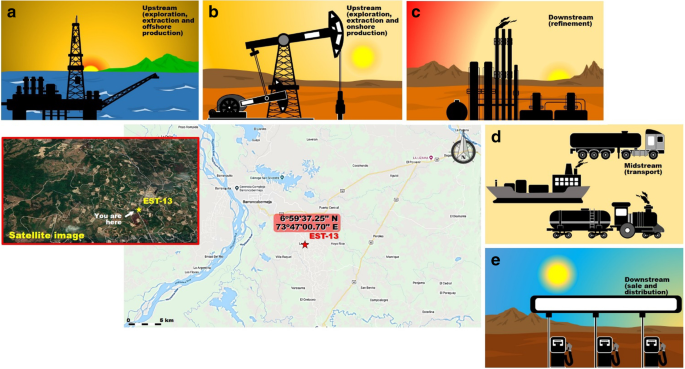

Patricia Rodríguez, a certified thermographer from Earthworks, conducted on-the-ground assessments in the Magdalena Medio during March and April 2023. Her investigation, part of a broader multi-country assessment of oil and gas impacts in South America, utilized an optical gas imaging (OGI) camera to reveal alarming levels of air contamination invisible to the naked eye.

"Shell's Paradise" Turns into "Ecopetrol's Nightmare"

The Magdalena Medio, an inter-Andean valley surrounding the vital Magdalena River, was once dubbed "Shell's paradise" between the 1930s and 1960s due to intense oil exploration. While multinational companies initially dominated, Ecopetrol eventually became the primary operator in the region, known for its rich biodiversity, fertile lands, and its crucial role as a sociocultural, environmental, and economic artery for Colombia.

Rodríguez's investigation, however, paints a grim picture of the region under Ecopetrol's dominance. The OGI camera documented significant emissions of methane and other volatile organic compounds (VOCs), including benzene, toluene, butane, and propane, from Ecopetrol and Mansarovar Energy (a Chinese-Indian company) operations in areas like Yondó, Puerto Boyacá, Barrancabermeja, and Puerto Wilches.

Invisible Threats, Tangible Impacts

The footage captured routine venting and incomplete burning of greenhouse gases, as well as unintended fugitive emissions from oil and gas infrastructure located alarmingly close to communities, waterways, and marshes. This proximity exposes residents and the delicate ecosystem to serious health and climate risks.

In Puerto Boyacá, emissions were seen venting from an open hatch atop an oil tank at a Mansarovar Energy facility near homes and a school. A leaking valve at an oil wellhead was found a mere 100 yards from a rural dwelling.

Local residents, speaking anonymously for fear of reprisal, reported a disturbing rise in childhood illnesses, including intense headaches, fainting spells, and suspected cases of cancer in fishing communities. The pervasive smell of hydrocarbons, likened to rotten eggs, disrupts sleep and daily life.

Despite a 2019 court ruling (tutela) granting residents constitutional protection and ordering companies to clean up pollution, community members claim that enforcement has been lacking. They describe a cycle of companies announcing well closures only to have other entities resume operations in their place. Repeated complaints to regulatory agencies like the National Agency for Environmental Permits (ANLA) often go unanswered, residents say.

Failed Regulations and Abandoned Contamination

Colombia adopted new regulations in February 2022 aimed at controlling methane emissions, including leak detection and repair protocols and the installation of vapor recovery units (VRUs). These rules were developed in collaboration with international organizations. However, Rodríguez's investigation found little evidence of VRUs in operation, and numerous instances of inefficient flaring and gas releases appeared to violate these very regulations.

The investigation also uncovered long-term contamination from abandoned sites. In the Palágua oil field, originally discovered by Texas Petroleum and later transferred to Ecopetrol, an abandoned well on private property was found bubbling and releasing hydrocarbon emissions. The property owner revealed at least eight oil and gas infrastructure sites on their land, along with extensive oil spills in a nearby marsh and mounds of oil-contaminated soil, with unclear remediation efforts.

Barrancabermeja: A City Living with Petroleum

In Barrancabermeja, home to Ecopetrol's largest refinery, the pervasive smell of petroleum underscored the company's dominance. While civil society mobilizations led to public air monitoring in 2012 following a spike in respiratory illnesses, local leaders claim that the air quality data remains inaccessible to non-experts, hindering their ability to definitively link health problems to the oil and gas industry.

OGI camera footage of the Barrancabermeja refinery revealed uncombusted hydrocarbon plumes being emitted directly into the air and incomplete combustion at flares, despite a recent $780 million upgrade aimed at improving efficiency and reducing emissions.

A Crossroads for Colombia's Energy Future

The "Crude Lies" report, the Iguana Papers, and Earthworks' investigation collectively paint a picture of entrenched wrongdoing, surveillance, and coercion within Colombia's oil and gas sector, hindering progress towards environmental justice and sustainability. The findings pose a significant challenge to President Gustavo Petro's ambitious plans for a transition away from fossil fuels and his commitment to halting new oil and gas extraction contracts. Recent exploratory operations in Colombia's Caribbean offshore waters further highlight the complexities and contradictions of this transition.

The evidence presented calls for a fundamental shift in Ecopetrol's business model, moving away from extraction and adopting a more collaborative and transparent approach with local communities. Environmental advocates argue that investors should consider divesting from the company until meaningful changes are implemented.

For the communities in Magdalena Medio and for Colombia as a whole, the possibility of a truly just energy transition hangs in the balance, demanding accountability and a decisive move towards a sustainable future.

[Copyright (c) Global Economic Times. All Rights Reserved.]