Many people misunderstand cholesterol's role in the body, often believing it's a simple case of "the lower, the better." However, recent research has nuanced this view, revealing that a balanced approach, guided by a doctor's advice, is key.

The Dangers of High LDL Cholesterol

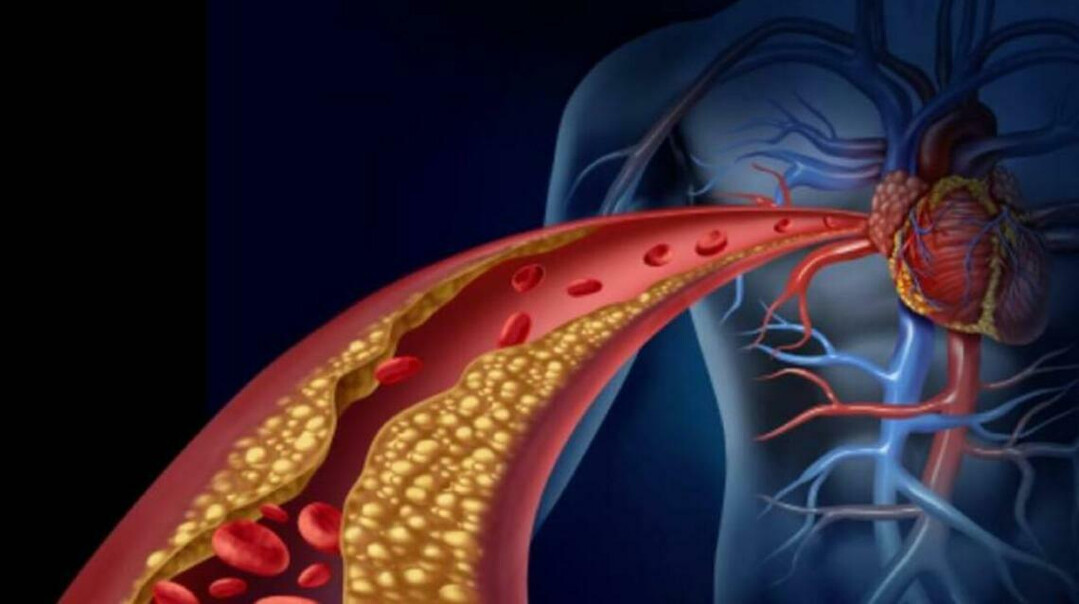

LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol, often called "bad cholesterol," is a critical metric for doctors. A healthy level is considered below 130 mg/dL, with 130-159 mg/dL being a borderline range and anything above 160 mg/dL a high-risk category. Elevated LDL levels can lead to atherosclerosis, or the hardening of arteries, which can increase the risk of serious cardiovascular events like angina, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

While some people may dismiss a slightly elevated LDL level, experts warn against this complacency. According to Dr. Kim Byung-jin of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, high LDL cholesterol and triglycerides can accelerate vascular aging and lead to sudden cardiac death. This is particularly true for those with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH).

Dr. Shizuya Yamashita, an expert on lipid abnormalities and atherosclerosis, emphasizes that a slightly high LDL level isn't always benign. The risk of developing atherosclerosis is influenced by other factors such as visceral obesity, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and age. While high LDL may not present with immediate symptoms, its prolonged presence can lead to a sudden, life-threatening cardiovascular event.

LDL: The Lower, the Better

The idea that high cholesterol is beneficial, particularly for the elderly, is a misconception. Studies show that as LDL levels increase, so does the risk of myocardial infarction, even in older adults. For instance, a long-term study of over 8,000 Japanese adults found that those with an LDL level of 140 mg/dL or higher were 3.8 times more likely to have a heart attack than those with a level below 80 mg/dL.

Some argue that very low LDL levels in the elderly can increase mortality. However, this is often linked to underlying health issues like malnutrition, hyperthyroidism, cancer, or liver disease. Powerful drugs, like PCSK9 inhibitors, can lower LDL levels to below 30 mg/dL, and studies have shown this reduces the incidence of heart attacks and strokes. Furthermore, people with a congenital deficiency of the PCSK9 protein, leading to extremely low LDL levels (around 24 mg/dL), have no health issues. These findings strongly support the notion that lower LDL levels are generally safer.

Rethinking HDL: Not Always "Good"

Cholesterol is essential for the body, forming cell membranes, hormones, and bile acids. The body produces about 70-80% of its own cholesterol, with the rest coming from diet. Cholesterol is transported throughout the body by lipoproteins. LDL carries cholesterol from the liver to the body, and HDL (high-density lipoprotein) collects excess cholesterol from blood vessel walls and returns it to the liver. This is why LDL is often called "bad" and HDL is called "good."

However, recent research is challenging the belief that a higher HDL level is always better. Clinical studies have shown that HDL can become dysfunctional when its levels exceed 100 mg/dL, making it unable to effectively collect cholesterol. This can paradoxically increase the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. Trials with drugs designed to raise HDL levels, known as CETP inhibitors, have also shown that while HDL levels increased, cardiovascular disease rates did not decrease, and in some cases, total mortality increased. While there's no official diagnosis for "high HDL," experts recommend a consultation with a specialist if your HDL level exceeds 100 mg/dL.

Familial Hypercholesterolemia: A Silent Threat

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is a genetic disorder that causes extremely high LDL levels from a young age due to a mutation in the LDL receptor gene. Though symptoms like xanthomas (yellowish skin nodules) and thickened Achilles tendons can appear, they often go unnoticed.

FH is categorized into two types: homozygous, inherited from both parents, and heterozygous, inherited from one. While homozygous FH is rare, heterozygous FH affects about one in 300 people. This condition can lead to myocardial infarction in men in their 20s and women in their 30s or 40s. Early detection and treatment are critical for preventing serious cardiovascular events in these individuals.

[Copyright (c) Global Economic Times. All Rights Reserved.]