Taiwan is significantly pulling ahead of South Korea in investment for advanced semiconductor manufacturing, particularly the 2-nanometer (nm) process, intensifying the competition in the global foundry market. This divergence is fueling Taiwan's robust economic growth, driven by its integrated semiconductor ecosystem and proactive government support, while South Korea faces structural headwinds and regulatory hurdles.

Massive Investment Bolsters Taiwan's Lead

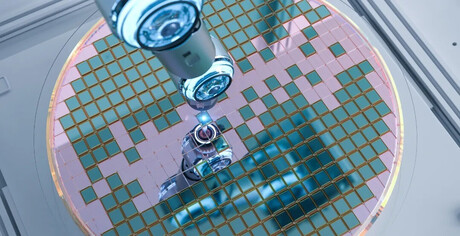

The core of Taiwan's current surge is TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company), the world's largest foundry. TSMC's commitment to cutting-edge technology is immense. The company has invested NT$1.5 trillion (approximately 67 trillion KRW) in its 2nm factory in Kaohsiung, a facility the size of 46 football fields. This site is slated to begin mass production of advanced chips—ordered by tech giants like NVIDIA, Apple, AMD, and Qualcomm—in the second half of this year, creating thousands of high-tech jobs.

Furthermore, TSMC has concrete plans to construct five additional fabrication plants (fabs) to support future advanced nodes, including the A16 process. The company has averaged five new fabs annually since 2021, a number expected to rise in 2025. This aggressive capacity expansion, concentrated across Taiwan's western coast, underscores a national-level strategy to dominate the future of advanced logic and packaging.

Taiwan's concentration on high-value sectors, including advanced logic and packaging, coupled with strong demand for AI-related chips from major global tech companies, is accelerating its economic growth. This is reflected in the Asian Development Bank (ADB)'s forecast, which projects Taiwan's 2025 economic growth rate at 5.1%, starkly contrasting with South Korea's mere 0.8% projection. Taiwan's successful strategy of pre-shipping inventory ahead of US tariff increases contributed to a 6.8% growth rate in the first half of this year, with net exports accounting for 3.2% of that growth.

Policy and Regulatory Divergence

Taiwan's success is not merely a corporate achievement; it is heavily underpinned by decisive state-led policy. The Taiwanese government implemented its version of the "CHIPS Act" in 2023, offering a substantial 25% tax credit on R&D investments for semiconductor companies. In contrast, South Korea's "K-Chips Act," which raised the corporate tax credit for facility investment by large semiconductor firms from 15% to only 20%, was only passed in January.

Labor regulation is another critical differentiating factor. Since 2017, Taiwan has allowed exceptions for extended working hours in advanced industries, including semiconductors. This flexibility was crucial to TSMC's historical "Nighthawk Project," a 24-hour, three-shift R&D operation that helped it outpace Samsung Electronics in foundry technology. South Korea, however, failed to pass a "Special Semiconductor Act" that would have granted similar exceptions to the 52-hour work week limit for semiconductor R&D personnel, leaving the industry constrained by labor and environmental regulations. Industry insiders point to overly strict regulations on construction—particularly in the desirable Seoul metropolitan area—and persistent issues with electricity supply and environmental permits as major obstacles to investment.

The Imperative for South Korea

The disparity in growth and investment highlights a widening gap in the foundry sector, where South Korea, a memory chip powerhouse, is struggling to build a balanced, vertically integrated ecosystem comparable to Taiwan's. Taiwan's strength lies in a comprehensive supply chain encompassing IC design (fabless), wafer manufacturing, packaging, and testing, with companies like MediaTek bolstering its design prowess.

South Korean industry officials warn that domestic fabless companies are increasingly opting for overseas foundries, underscoring the need for a domestic foundry-centric ecosystem. Calls are mounting for the South Korean government to offer greater incentives for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the materials, parts, and equipment (So-Bu-Jang) sector to foster a sustainable and self-sufficient semiconductor supply chain. Failure to address these systemic issues, coupled with an over-reliance on a few high-value products like High Bandwidth Memory (HBM), risks further marginalizing South Korea's position in the high-stakes global semiconductor race.

[Copyright (c) Global Economic Times. All Rights Reserved.]